The biggest contribution scientists can make to #scicomm related to the newly released IPCC Sixth Assessment report, is to stop talking about the multi-model mean.

[Read more…] about #NotAllModelsClimate modelling

We are not reaching 1.5ºC earlier than previously thought

Guest commentary by Malte Meinshausen, Zebedee Nicholls, and Piers Forster

Of all the troubling headlines emerging from the release of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) WG1 report, one warning will surely dominate headlines in the next days and weeks: Earth is likely to reach the crucial 1.5℃ warming limit in the early 2030s.

In 2018, the IPCC Special Report on 1.5C warming stated in its summary for policy makers that the world was likely to cross the 1.5℃ threshold between 2030 and 2052, if current warming trends continue.

In this latest AR6, a more comprehensive assessment was undertaken to estimate when a warming level of 1.5℃ might be reached. As a result, some early media reports suggest 1.5ºC warming is now anticipated 10-years earlier than previously assumed (AFR, THE TIMES).

We want to explain here why that is not backed up by a rigorous comparison of the SR1.5 and AR6 reports. In fact, the science in the previous SR1.5 report and the new AR6 report are remarkably consistent.

[Read more…] about We are not reaching 1.5ºC earlier than previously thoughtThe IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

Climate scientists are inordinately excited by the release of a new IPCC report (truth be told, that’s a bit odd – It’s a bit like bringing your end-of-(seven)-year project home and waiting anxiously to see how well it will be received). So, in an uncharacteristically enthusiastic burst of effort, we have a whole suite of posts on the report for you to read.

- AR6 of the Best. Half a dozen takeaways from the report from Gavin

- New (8/13): Sea Level Rise in AR6 from Stefan

- A Tale of Two Hockey Sticks by Mike

- #NotAllModels discusses the use (and mis-use) of the CMIP6 ensemble by Gavin

- We are not reaching 1.5ºC earlier than previously thought from guest authors Malte Meinshausen, Zebedee Nicholls and Piers Forster

- New (8/12): Deciphering the SPM AR6 WG1 Code by Rasmus

- New (8/12): A deep dive into the IPCC’s updated carbon budget numbers from guest author Joeri Rogelj

If/when we add some more commentary as we digest the details and we see how the report is being discussed, we’ll link it from here. Feel free to discuss general issues with the report in the comments here, and feel free to suggest further deep dives we might pursue.

Climate adaptation should be based on robust regional climate information

Climate adaptation steams forward with an accelerated speed that can be seen through the Climate Adaptation Summit in January (see previous post), the ECCA 2021 in May/June, and the upcoming COP26. Recent extreme events may spur this development even further (see previous post about attribution of recent heatwaves).

To aid climate adaptation, Europe’s Climate-Adapt programme provides a wealth of resources, such as guidance, case studies and videos. This is a good start, but a clear and transparent account on how to use the actual climate information for adaptation seems to be missing. How can projections of future heatwaves or extreme rainfall help practitioners, and how to interpret this kind of information?

[Read more…] about Climate adaptation should be based on robust regional climate informationRapid attribution of PNW heatwave

Summary: It was almost impossible for the temperatures seen recently in the Pacific North West heatwave to have occurred without global warming. And only improbable with it.

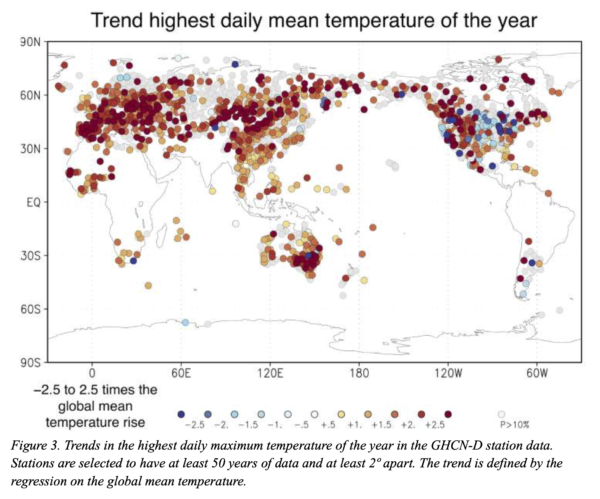

It’s been clear for at least a decade that global warming has been in general increasing the intensity of heat waves, with clear trends in observed maximum temperatures that match what climate models have been predicting. For the specific situation in the Pacific NorthWest at the end of June, we now have the first attribution analysis from the World Weather Attribution group – a consortium of climate experts from around the world working on extreme event attribution. Their preprint (Philip et al.) is available here.

The Rise and Fall of the “Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation”

Two decades ago, in an interview with science journalist Richard Kerr for the journal Science, I coined the term the “Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation” (AMO) to describe an internal oscillation in the climate system resulting from interactions between North Atlantic ocean currents and wind patterns. These interactions were thought to lead to alternating decades-long intervals of warming and cooling centered in the extra-tropical North Atlantic that play out on 40-60 year timescales (hence the name). Think of the purported AMO as a much slower relative of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO), with a longer timescale of oscillation (multidecadal rather than interannual) and centered in a different region (the North Atlantic rather than the tropical Pacific).

Today, in a research article published in the same journal Science, my colleagues and I have provided what we consider to be the most definitive evidence yet that the AMO doesn’t actually exist.

[Read more…] about The Rise and Fall of the “Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation”Laschamps-ing at the bit

A placeholder to provide some space to discuss the paper last week (Cooper et al, 2021) on the putative climate consequences of the Laschamps Geomagnetic Excursion, some 42,000 yrs ago.

There was some rather breathless reporting on this paper, but there were also a lot of sceptical voices – not of the main new result (a beautiful new 14C dataset from a remarkable kauri tree log found in New Zealand), but of the more speculative implications – both climatically and anthropologically.

On twitter there were some good threads covering multiple aspects of the paper (and the lead author):

The paper presents some modeling of the impact of the geomagnetic change – mainly affecting solar energetic particles in the stratsophere which leads to some ozone depletion (but not much). They also model what might have happened if on top of the geomagnetic change, there was…

— Gavin Schmidt (@ClimateOfGavin) February 19, 2021

So, do you all know who the lead author is of that 42,000-yr climate event Science paper? It's this guy. https://t.co/2K50tzovAy

— Jessica Tierney (@leafwax) February 21, 2021

"A global environmental crisis 42,000 years ago" in context. pic.twitter.com/49HAmQbzGw

— Thomas Bauska (@tinyicybubbles) February 19, 2021

So, I've started tracking down the citations in this Magnetodeth paper. It will be a surprise to no one that the papers on genetic bottlenecks do not support the 42,000-year-ago event that the new paper says they do.

— John Hawks (@johnhawks) February 19, 2021

But let me make a couple of different points. We have occasionally discussed the Laschamps event here as a counter-example to the notion that changes in galactic cosmic rays have a major impact on climate. A reversal or near-reversal of the geomagnetic field would be expected to greatly increase the GCR getting to the lower atmosphere – in far greater amounts than over a solar cycle, or grand solar minimum (like the Maunder Minimum). So if people want to postulate a big role for GCR there, they needed to explain why there wasn’t a much bigger signal at 42kya too. These authors are thus not the only people to have looked for significant climate impacts at this time. They are perhaps the first to claim to have found them…

To be clear, the modeling that was done in this paper was good (if extreme) and suggested that the geomagnetic event combined with a severe grand solar minimum (much bigger than the Maunder minimum) would cause significant depletion of the ozone layer and some shifts in the annular modes. But the ozone depletion is less than we’ve seen due to anthropogenic ozone depletion since the 1980s, and the surface climate changes don’t seem very significant at all – especially compared to the massive variability exhibited in the ice cores throughout the last ice age (particularly in Marine Isotope Stage 3 – the Dansgaard-Oeschgar events). At best these are nuanced and subtle climate effects, and certainly not anything apocalyptic (despite Stephen Fry’s dulcet tones).

Finally, it should be called the Laschamps event (with a final, and etymologically correct, ‘s’) after the village in the Auvergne where it was first identified. There is unfortunately 50 years of legacy references to the “Laschamp” excursion, but hopefully it isn’t too late to fix!

References

- A. Cooper, C.S.M. Turney, J. Palmer, A. Hogg, M. McGlone, J. Wilmshurst, A.M. Lorrey, T.J. Heaton, J.M. Russell, K. McCracken, J.G. Anet, E. Rozanov, M. Friedel, I. Suter, T. Peter, R. Muscheler, F. Adolphi, A. Dosseto, J.T. Faith, P. Fenwick, C.J. Fogwill, K. Hughen, M. Lipson, J. Liu, N. Nowaczyk, E. Rainsley, C. Bronk Ramsey, P. Sebastianelli, Y. Souilmi, J. Stevenson, Z. Thomas, R. Tobler, and R. Zech, "A global environmental crisis 42,000 years ago", Science, vol. 371, pp. 811-818, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8677

Regional information for society (RifS) and unresolved issues

It’s encouraging to note the growing interest for regional climate information for society and climate adaptation, such as recent advances in the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP), the climate adaptation summit CAS2021, and the new Digital Europe. These efforts are likely to boost the Global Framework for Climate Services (GFCS) needed as a guide to decision-makers on matters influenced by weather and climate.

[Read more…] about Regional information for society (RifS) and unresolved issuesUpdate day 2021

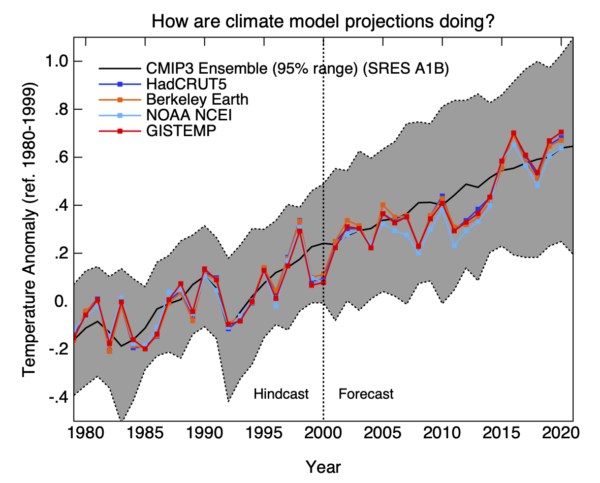

As is now traditional, every year around this time we update the model-observation comparison page with an additional annual observational point, and upgrade any observational products to their latest versions.

A couple of notable issues this year. HadCRUT has now been updated to version 5 which includes polar infilling, making the Cowtan and Way dataset (which was designed to address that issue in HadCRUT4) a little superfluous. Going forward it is unlikely to be maintained so, in a couple of figures, I have replaced it with the new HadCRUT5. The GISTEMP version is now v4.

For the comparison with the Hansen et al. (1988), we only had the projected output up to 2019 (taken from fig 3a in the original paper). However, it turns out that fuller results were archived at NCAR, and now they have been added to our data file (and yes, I realise this is ironic). This extends Scenario B to 2030 and Scenario A to 2060.

Nothing substantive has changed with respect to the satellite data products, so the only change is the addition of 2020 in the figures and trends.

So what do we see? The early Hansen models have done very well considering the uncertainty in total forcings (as we’ve discussed (Hausfather et al., 2019)). The CMIP3 models estimates of SAT forecast from ~2000 continue to be astoundingly on point. This must be due (in part) to luck since the spread in forcings and sensitivity in the GCMs is somewhat ad hoc (given that the CMIP simulations are ensembles of opportunity), but is nonetheless impressive.

The forcings spread in CMIP5 was more constrained, but had some small systematic biases as we’ve discussed Schmidt et al., 2014. The systematic issue associated with the forcings and more general issue of the target diagnostic (whether we use SAT or a blended SST/SAT product from the models), give rise to small effects (roughly 0.1ºC and 0.05ºC respectively) but are independent and additive.

The discrepancies between the CMIP5 ensemble and the lower atmospheric MSU/AMSU products are still noticeable, but remember that we still do not have a ‘forcings-adjusted’ estimate of the CMIP5 simulations for TMT, though work with the CMIP6 models and forcings to address this is ongoing. Nonetheless, the observed TMT trends are very much on the low side of what the models projected, even while stratospheric and surface trends are much closer to the ensemble mean. There is still more to be done here. Stay tuned!

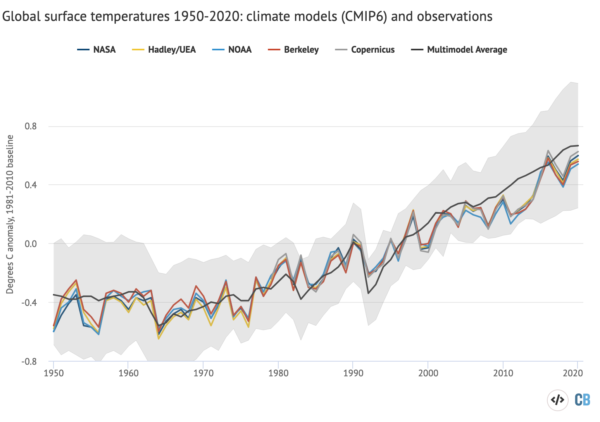

The results from CMIP6 (which are still being rolled out) are too recent to be usefully added to this assessment of forecasts right now, though some compilations have now appeared:

The issues in CMIP6 related to the excessive spread in climate sensitivity will need to be looked at in more detail moving forward. In my opinion ‘official’ projections will need to weight the models to screen out those ECS values outside of the constrained range. We’ll see if other’s agree when the IPCC report is released later this year.

Please let us know in the comments if you have suggestions for improvements to these figures/analyses, or suggestions for additions.

References

- Z. Hausfather, H.F. Drake, T. Abbott, and G.A. Schmidt, "Evaluating the Performance of Past Climate Model Projections", Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 47, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085378

- G.A. Schmidt, D.T. Shindell, and K. Tsigaridis, "Reconciling warming trends", Nature Geoscience, vol. 7, pp. 158-160, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2105

2020 vision

No-one needs another litany of all the terrible things that happened this year, but there are three areas relevant to climate science that are worth thinking about:

- What actually happened in climate/weather (and how they can be teased apart). There is a good summary on the BBC radio Discover program covering wildfires, heat waves, Arctic sea ice, the hurricane season, etc. featuring Mike Mann, Nerlie Abram, Sarah Perkins-Kilpatrick, Steve Vavrus and others. In particular, there were also some new analyses of hurricanes (their rapid intensification, slowing, greater precipitation levels etc.), as well as the expanding season for tropical storms that may have climate change components. Yale Climate Connections also has a good summary.

- The accumulation of CMIP6 results. We discussed some aspects of these results extensively – notably the increased spread in Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity, but there is a lot more work to be done on analyzing the still-growing database that will dominate the discussion of climate projections for the next few years. Of particular note will be the need for more sophisticated analyses of these model simulations that take into account observational constraints on ECS and a wider range of future scenarios (beyond just the SSP marker scenarios that were used in CMIP). These issues will be key for the upcoming IPCC 6th Assessment Report and the next National Climate Assessment.

- The intersection of climate and Covid-19.

- The direct connections are clear – massive changes in emissions of aerosols, short-lived polluting gases (like NOx) and CO2 – mainly from reductions in transportation. Initial results demonstrated a clear connection between cleaner air and the pandemic-related restrictions and behavioural changes, but so far the impacts on temperature or other climate variables appear to be too small to detect (Freidlingstein et al, 2020). The impact on global CO2 emissions (LeQuere et al, 2020) has been large (about 10% globally) – but not enough to stop CO2 concentrations from continuing to rise (that would need a reduction of more like 70-80%). Since the impact from CO2 is cumulative this won’t make a big difference in future temperatures unless it is sustained through post-pandemic changes.

- The metaphorical connections are also clear. The instant rise of corona virus-denialism, the propagation of fringe viewpoints from once notable scientists, petitions to undermine mainstream epidemiology, politicized science communications, and the difficulty in matching policy to science (even for politicians who want to just ‘follow the science’), all seem instantly recognizable from a climate change perspective. The notion that climate change was a uniquely wicked problem (because of it’s long term and global nature) has evaporated as quickly as John Ioannidis’ credibility.

I need to take time to note that there has been human toll of Covid-19 on climate science, ranging from the famous (John Houghton) to the families of people you never hear about in the press but whose work underpins the data collection, analysis and understanding we all rely on. This was/is a singular tragedy.

With the La Niña now peaking in the tropical Pacific, we can expect a slightly cooler year in 2021 and perhaps a different character of weather events, though the long-term trends will persist. My hope is that the cracks in the system that 2020 has revealed (across a swathe of issues) can serve as an motivation to improve resilience, equity and planning, across the board. That might well be the most important climate impact of all.

A happier new year to you all.

References

- P.M. Forster, H.I. Forster, M.J. Evans, M.J. Gidden, C.D. Jones, C.A. Keller, R.D. Lamboll, C.L. Quéré, J. Rogelj, D. Rosen, C. Schleussner, T.B. Richardson, C.J. Smith, and S.T. Turnock, "Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19", Nature Climate Change, vol. 10, pp. 913-919, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0

- C. Le Quéré, R.B. Jackson, M.W. Jones, A.J.P. Smith, S. Abernethy, R.M. Andrew, A.J. De-Gol, D.R. Willis, Y. Shan, J.G. Canadell, P. Friedlingstein, F. Creutzig, and G.P. Peters, "Temporary reduction in daily global CO2 emissions during the COVID-19 forced confinement", Nature Climate Change, vol. 10, pp. 647-653, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0797-x