The biggest contribution scientists can make to #scicomm related to the newly released IPCC Sixth Assessment report, is to stop talking about the multi-model mean.

[Read more…] about #NotAllModelsAR6 of the best

Half a dozen takeaways from a first read of the new IPCC AR6 report.

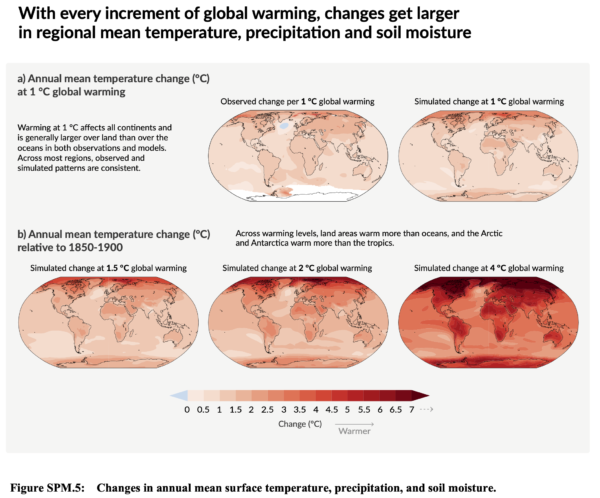

As climate scientists we tend to look at the IPCC reports a little differently than the general public might. Here are a few things that mark this report out from previous versions that relate to issues we’ve discussed here before:

- Extreme events are increasingly connected to climate (duh!)

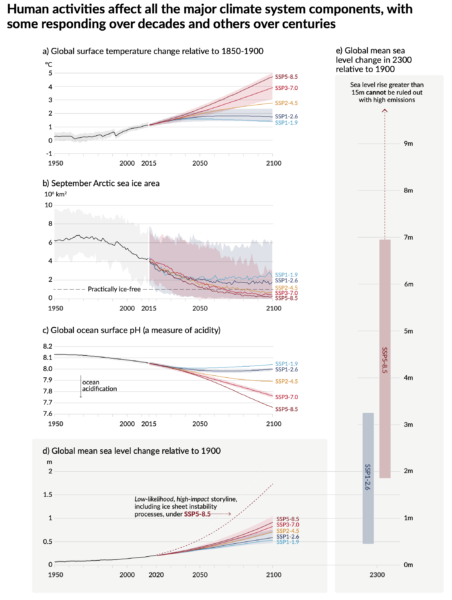

- Sea level rise is a big deal

- Use, abuse and misuse of the CMIP6 ensemble

- The radiative forcing bar chart has gone full circle

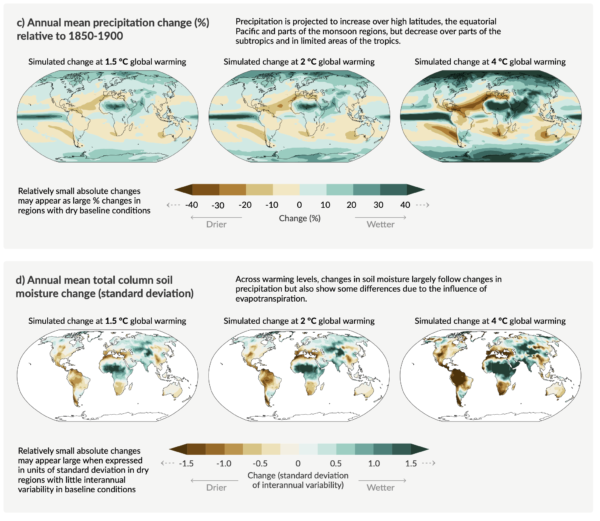

- Droughts and floods are complicated

- Don’t mention the hiatus

There are other things that will get the headlines (the expected time before we get to 1.5ºC or 2ºC, the headline SLR numbers, the ‘unprecedented rate’ statement, constraints on climate sensitivity, carbon cycle feedbacks, the implications for the carbon budgets etc.), and other things worth noting – for instance, the much better and more direct graphics that they have clearly worked on a lot. As usual, most of the headlines will also focus on the Summary For Policy Makers (SPM) which was approved word by word by the governments over the last two weeks (full disclosure, I was advising the US delegation), but the full report will be worth dipping into over the next few months (there is a lot there to digest!).

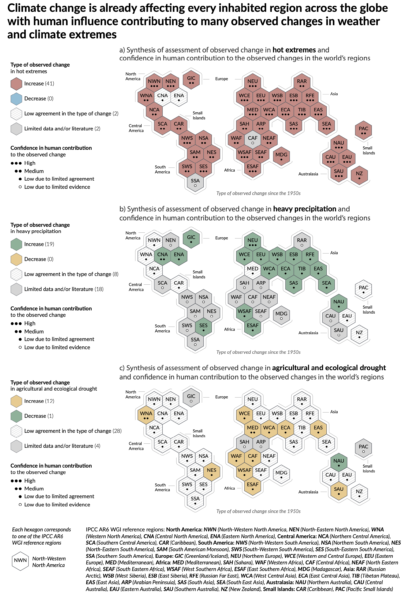

1. Extremes: Back in 2012, the literature assessed by AR5 connecting changes in extremes to climate change was scant. As we wrote at the time, attribution of single events was difficult and experimental. But as was exemplified by the recent reaction to the PNW heatwave, things have moved on considerably. This has allowed the IPCC authors to produce regional assessments of past changes in heat extremes, intense precipitation and agricultural/ecological drought in drying regions (see below for a discussion on what that means), and produce assessed projections of a whole suite of what they call Climate-impact Drivers (CIDs) – which includes floods, marine heatwaves etc. People who (even a couple of weeks ago) were quoting the AR5 statements on extremes as if that was current are going to have to update their talking points (that is, of course, if they care about correctly reflecting the most up-to-date science…).

For example, IPCC finds that Northern Europe, Western Central Europe and Eastern Europe all show an observed increase in heavy precipitation events, such as the one causing the recent massive flooding in Germany and Belgium. Western Central Europe is one of the few regions where both an increase in extreme precipitation and in drought have already been documented. The IPCC notes that it’s the most rare and severe extremes which are expected to show the biggest percentage increase in frequency (see this past RealClimate post).

2. Sea Level Rise: The previous IPCC reports, notably AR4 and AR5 (to a lesser extent), have had a hard time dealing with SLR. This has been due to multiple issues, including a historical lack of comprehensive literature to assess, very uncertain observations of ice sheets, and difficultlies in blending different lines of evidence. In this report they’ve tried much harder to put the data together more coherently, there is more evidence, and they haven’t shied away from being explicit about the low-likelihood/high-impact possibilities (mostly associated with a collapse of WAIS). Literally, the sea level projection runs off the page… (Stefan will have a more detailed assessment later).

3. Use, Abuse and Misuse of the CMIP6 ensemble: I’ll discuss this in more detail in another post, but I want to commend the IPCC authors for dealing with the increased spread in the CMIP6 ensemble climate sensitivity in two very sensible ways. Firstly, the use constrained projections for all the temperature (and sea level) time series out to 2100 allows them to downweight (effectively to zero) the high (and low) ECS models that are outside of the assessed range (note this would not have made much (if any) difference in CMIP5). Secondly, they choose to focus on the patterns of change, not for certain time-periods, but for specific “Global Warming Levels” (GWLs). That is to say, what the expected pattern of rainfall (for instance) might be when the global mean temperature reaches 1.5ºC, or 2ºC or 4ºC etc. This allows them to include all the models (including good models with improved climatologies that happen to have high ECS like the NCAR CESM2 or the HadGEM3 models). Additionally, the GWL impacts plots neatly divorce the limited scenarios that were used in CMIP6 from the ability to assess impacts. Thus if policy-makers or others want to explore the impacts of other scenarios that might reach specific warming levels earlier or later than any one of the SSPs, they can do so easily, without having to rerun the models.

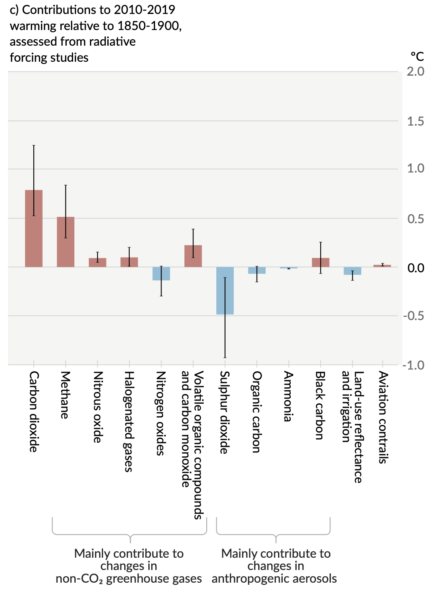

4. The radiative forcing bar chart has gone full circle: Almost every IPCC report has a version of the radiative bar chart showing the contributions over the historical period of all the different forcings (greenhouse gases, aerosols, solar, etc.). Every iteration has changed in trivial and sometimes substantive ways (I wrote a history of this a few years back), for instance, it’s oscillated from a vertical or horizontal presentation for no apparent reason, and the individual components have followed the scientific views of what was important. In this SPM it appears in Fig. SPM 2c and has gone back to being vertical. They have stuck with the contributions by emission (as opposed to concentration – something we pushed for last time), but the novelty here is that they are plotting the estimated temperature impact from each of the contributions (using the radiative forcing, the assessed climate sensitivity and an simple impulse-response model). Oddly enough this is most reminiscent of the very first bar chart that appeared in Hansen et al. (1981) which can be seen here.

5. Droughts and floods are complicated: The picture on droughts and floods is more complicated than most people think. First, there is a great deal of regional variation, second the historical metrics we use to assess drought (such as the Palmer Drought Severity Index) don’t perform very well in a changing climate, and third the attribution of meteorological or agricultural or ecological drought varies as well. Analyses that average over too wide an area, or that look at the wrong metrics, will come to erroneous conclusions. The IPCC authors went to a lot of trouble to disentangle this and the assessment in Fig. SPM3 of evidence for observed drought changes focuses specifically on agricultural and ecological drought (based on soil moisture), as opposed to hydrological drought (runoff) or meteorological drought (based on rainfall). This is because we don’t see strong attribution in total rainfall amounts, but we do in evaporative demand (which depends on temperature). Thus when we have a longterm precipitation anomaly (such as in the American South West (WNA in the hexagon plot above)), we can’t (yet) attribute the rainfall change, but we can attribute the soil moisture change. Floods are also complicated because they too don’t solely depend on a single factor (such as intense precipitation) – but instead are a function of prior state of soil moisture, water management practices and other hyper-local effects. Work here will continue to advance, but the picture is clear only in a few regions so far.

6. Don’t mention the hiatus: Readers will probably remember the prominence of the ‘hiatus’ in the discussions around the AR5 report (written in 2013) (see here, here, or here). Due in part to (IMO) an over-reliance on a single temperature record (HadCRUT4), and (it turns out) non-climatic biases in the ocean temperature records, the trends from 1998-2012 got a specific call out in the AR5 SPM:

In addition to robust multi-decadal warming, global mean surface temperature exhibits substantial decadal and interannual variability (see Figure SPM.1). Due to natural variability, trends based on short records are very sensitive to the beginning and end dates and do not in general reflect long-term climate trends. As one example, the rate of warming over the past 15 years (1998–2012; 0.05 [–0.05 to 0.15] °C per decade), which begins with a strong El Niño, is smaller than the rate calculated since 1951 (1951–2012; 0.12 [0.08 to 0.14] °C per decade)5. {2.4}

Section B.1, SPM AR5

The observed reduction in surface warming trend over the period 1998 to 2012 as compared to the period 1951 to 2012, is due in roughly equal measure to a reduced trend in radiative forcing and a cooling contribution from natural internal variability, which includes a possible redistribution of heat within the ocean (medium confidence). The reduced trend in radiative forcing is primarily due to volcanic eruptions and the timing of the downward phase of the 11-year solar cycle. However, there is low confidence in quantifying the role of changes in radiative forcing in causing the reduced warming trend. There is medium confidence that natural internal decadal variability causes to a substantial degree the difference between observations and the simulations; the latter are not expected to reproduce the timing of natural internal variability. There may also be a contribution from forcing inadequacies and, in some models, an overestimate of the response to increasing greenhouse gas and other anthropogenic forcing (dominated by the effects of aerosols). {9.4, Box 9.2, 10.3, Box 10.2, 11.3}

Section D.1, SPM, AR5

Now however, the updates to the historical warming, the use of four datasets instead of one, and of course, the series of record breaking years subsequently (2014, 2015, 2016/2020), the issue of variability in decadal trends is no longer so salient. The shifts in the quoted trends (1998-2012 is now 0.12ºC/decade, 1951-2012 is 0.13ºC, HadCRUT5) underlines the trivialness of the issue. To be fair, there is one mention of the hiatus in the AR6 Technical Summary:

The observed slower global surface temperature increase (relative to preceding and following periods) in the 1998–2012 period, sometimes referred to as ‘the hiatus’, was temporary (very high confidence). The increase in global surface temperature during the 1998–2012 period is also greater in the data sets used in the AR6 assessment than in those available at the time of AR5. Using these updated observational data sets and a like- for-like consistent comparison of simulated and observed global surface temperature, all observed estimates of the 1998–2012 trend lie within the very likely range of CMIP6 trends. Since 2012, global surface temperature has warmed strongly, with the past five years (2016–2020) being the hottest five-year period between 1850 and 2020 (high confidence). {2.3.1, 3.3.1, 3.5.1, Cross-Chapter Box 3.1}

AR6 Cross-Section Box TS.1

Let this episode stand as a clear reminder for assessment reports not to get ahead of the science…

And so to bed…

Finally, let me finish up with a couple of personal observations. This was the first IPCC report where I was involved in the SPM approval process, and while that was frustrating at times, the vast majority of delegates were obviously focussed on getting the best summary consistent with the science that they could. Obviously, some countries had specific sensitivities, but seeing the negotiations on how those issues could be finessed while sticking to language that the authors approved of was impressive. In particular, the chairing of the meeting by Valerie Masson-Delmotte was a masterclass in effective meeting strategies. The virtual nature of the proceedings means that this was undoubtedly the SPM approval session with the lowest carbon footprint which might serve as a model for future efforts. However, the ‘all time zone’ nature of the proceedings and the very interrupted nature of my resulting sleep patterns has left a mark on pretty much everyone involved. Forgive me if I sleep in for the rest of this week…

References

- J. Hansen, D. Johnson, A. Lacis, S. Lebedeff, P. Lee, D. Rind, and G. Russell, "Climate Impact of Increasing Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide", Science, vol. 213, pp. 957-966, 1981. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.213.4511.957

Why is future sea level rise still so uncertain?

Three new papers in the last couple of weeks have each made separate claims about whether sea level rise from the loss of ice in West Antarctica is more or less than you might have thought last month and with more or less certainty. Each of these papers make good points, but anyone looking for coherent picture to emerge from all this work will be disappointed. To understand why, you need to know why sea level rise is such a hard problem in the first place, and appreciate how far we’ve come, but also how far we need to go.

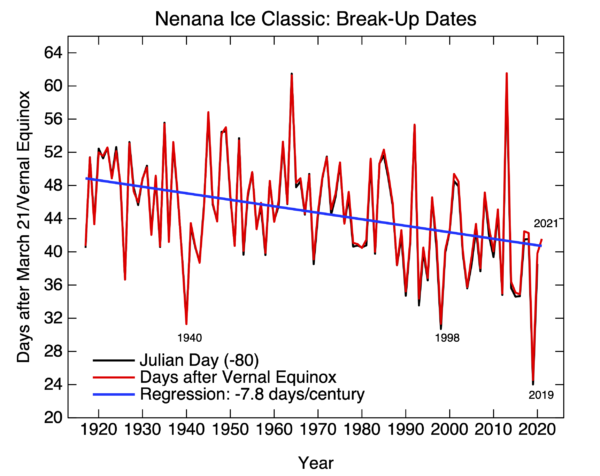

Nenana Ice Classic 2021

And…. it’s that time again. The clock stopped on the Nenana ice classic this afternoon (April 30, 12:50pm AT). This is pretty much on trend and unsurprising given the relatively slightly cool winter in Alaska. The jackpot on offer this year was $233,591 but will likely be shared among several winners. This year’s ‘break up’ is a little odd, since the ice moved sufficiently to trigger the clock, but not enough to actually topple the tripod (which is still visible as this is being written (9pm ET) – Update 10:30pm ET: gone now though!). But, the rules are the rules…

The trends in the break up date is about 8 days earlier per century (±4), estimated over the whole record, but substantially faster over the last 50 years (16 ± 12 days/century, 95% CI).

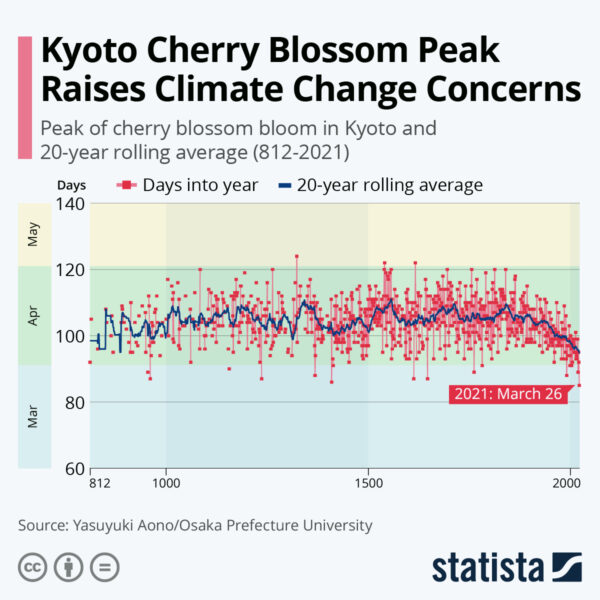

Other phenological records show similar trends, notably the longest cherry blossom record from Kyoto which dates back to 9th Century, and which had a record earliest peak bloom this year and a clear trend over the last few decades:

Feel free to link to your favorite such record in the comments…

Laschamps-ing at the bit

A placeholder to provide some space to discuss the paper last week (Cooper et al, 2021) on the putative climate consequences of the Laschamps Geomagnetic Excursion, some 42,000 yrs ago.

There was some rather breathless reporting on this paper, but there were also a lot of sceptical voices – not of the main new result (a beautiful new 14C dataset from a remarkable kauri tree log found in New Zealand), but of the more speculative implications – both climatically and anthropologically.

On twitter there were some good threads covering multiple aspects of the paper (and the lead author):

The paper presents some modeling of the impact of the geomagnetic change – mainly affecting solar energetic particles in the stratsophere which leads to some ozone depletion (but not much). They also model what might have happened if on top of the geomagnetic change, there was…

— Gavin Schmidt (@ClimateOfGavin) February 19, 2021

So, do you all know who the lead author is of that 42,000-yr climate event Science paper? It's this guy. https://t.co/2K50tzovAy

— Jessica Tierney (@leafwax) February 21, 2021

"A global environmental crisis 42,000 years ago" in context. pic.twitter.com/49HAmQbzGw

— Thomas Bauska (@tinyicybubbles) February 19, 2021

So, I've started tracking down the citations in this Magnetodeth paper. It will be a surprise to no one that the papers on genetic bottlenecks do not support the 42,000-year-ago event that the new paper says they do.

— John Hawks (@johnhawks) February 19, 2021

But let me make a couple of different points. We have occasionally discussed the Laschamps event here as a counter-example to the notion that changes in galactic cosmic rays have a major impact on climate. A reversal or near-reversal of the geomagnetic field would be expected to greatly increase the GCR getting to the lower atmosphere – in far greater amounts than over a solar cycle, or grand solar minimum (like the Maunder Minimum). So if people want to postulate a big role for GCR there, they needed to explain why there wasn’t a much bigger signal at 42kya too. These authors are thus not the only people to have looked for significant climate impacts at this time. They are perhaps the first to claim to have found them…

To be clear, the modeling that was done in this paper was good (if extreme) and suggested that the geomagnetic event combined with a severe grand solar minimum (much bigger than the Maunder minimum) would cause significant depletion of the ozone layer and some shifts in the annular modes. But the ozone depletion is less than we’ve seen due to anthropogenic ozone depletion since the 1980s, and the surface climate changes don’t seem very significant at all – especially compared to the massive variability exhibited in the ice cores throughout the last ice age (particularly in Marine Isotope Stage 3 – the Dansgaard-Oeschgar events). At best these are nuanced and subtle climate effects, and certainly not anything apocalyptic (despite Stephen Fry’s dulcet tones).

Finally, it should be called the Laschamps event (with a final, and etymologically correct, ‘s’) after the village in the Auvergne where it was first identified. There is unfortunately 50 years of legacy references to the “Laschamp” excursion, but hopefully it isn’t too late to fix!

References

- A. Cooper, C.S.M. Turney, J. Palmer, A. Hogg, M. McGlone, J. Wilmshurst, A.M. Lorrey, T.J. Heaton, J.M. Russell, K. McCracken, J.G. Anet, E. Rozanov, M. Friedel, I. Suter, T. Peter, R. Muscheler, F. Adolphi, A. Dosseto, J.T. Faith, P. Fenwick, C.J. Fogwill, K. Hughen, M. Lipson, J. Liu, N. Nowaczyk, E. Rainsley, C. Bronk Ramsey, P. Sebastianelli, Y. Souilmi, J. Stevenson, Z. Thomas, R. Tobler, and R. Zech, "A global environmental crisis 42,000 years ago", Science, vol. 371, pp. 811-818, 2021. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.abb8677

Don’t climate bet against the house

Decades ago (it seems) when perhaps it was still possible to have good faith disagreements about the attribution of current climate trends, James Annan wrote a post here summarizing the thinking and practice of Climate Betting. That led to spate of wagers on continued global warming (a summary of his bets through 2005 and attempts to set up others is here).

There were earlier bets, the most well known perhaps was the one for $100 between Hugh Ellsaesser and Jim Hansen in 1989 on whether there would be a new temperature record within three years. There was (1990), and Ellsaesser paid up in January 1991 (Kerr, 1991). But these more recent bets were more extensive.

[Read more…] about Don’t climate bet against the houseReferences

- R.A. KERR, "Global Temperature Hits Record Again", Science, vol. 251, pp. 274-274, 1991. http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.251.4991.274

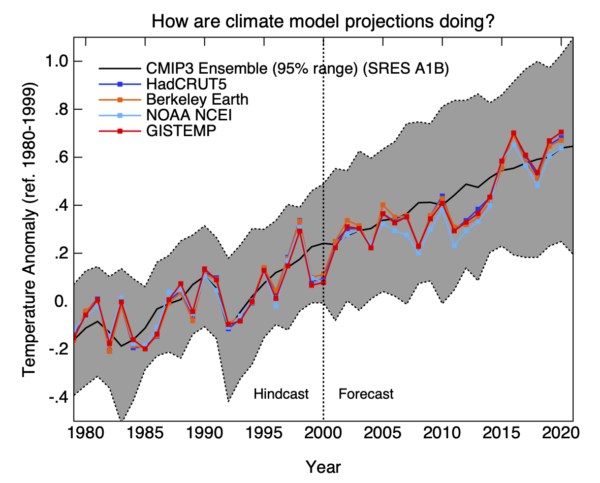

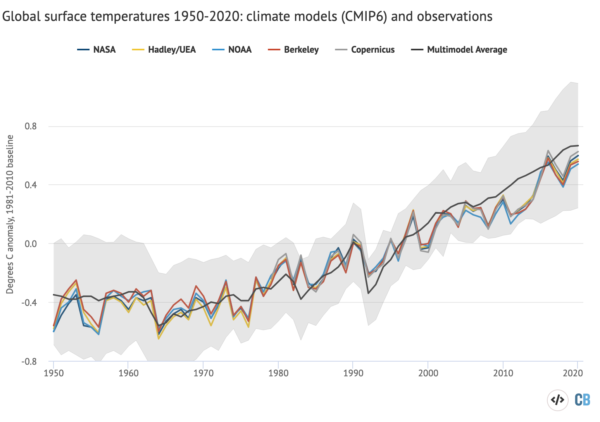

Update day 2021

As is now traditional, every year around this time we update the model-observation comparison page with an additional annual observational point, and upgrade any observational products to their latest versions.

A couple of notable issues this year. HadCRUT has now been updated to version 5 which includes polar infilling, making the Cowtan and Way dataset (which was designed to address that issue in HadCRUT4) a little superfluous. Going forward it is unlikely to be maintained so, in a couple of figures, I have replaced it with the new HadCRUT5. The GISTEMP version is now v4.

For the comparison with the Hansen et al. (1988), we only had the projected output up to 2019 (taken from fig 3a in the original paper). However, it turns out that fuller results were archived at NCAR, and now they have been added to our data file (and yes, I realise this is ironic). This extends Scenario B to 2030 and Scenario A to 2060.

Nothing substantive has changed with respect to the satellite data products, so the only change is the addition of 2020 in the figures and trends.

So what do we see? The early Hansen models have done very well considering the uncertainty in total forcings (as we’ve discussed (Hausfather et al., 2019)). The CMIP3 models estimates of SAT forecast from ~2000 continue to be astoundingly on point. This must be due (in part) to luck since the spread in forcings and sensitivity in the GCMs is somewhat ad hoc (given that the CMIP simulations are ensembles of opportunity), but is nonetheless impressive.

The forcings spread in CMIP5 was more constrained, but had some small systematic biases as we’ve discussed Schmidt et al., 2014. The systematic issue associated with the forcings and more general issue of the target diagnostic (whether we use SAT or a blended SST/SAT product from the models), give rise to small effects (roughly 0.1ºC and 0.05ºC respectively) but are independent and additive.

The discrepancies between the CMIP5 ensemble and the lower atmospheric MSU/AMSU products are still noticeable, but remember that we still do not have a ‘forcings-adjusted’ estimate of the CMIP5 simulations for TMT, though work with the CMIP6 models and forcings to address this is ongoing. Nonetheless, the observed TMT trends are very much on the low side of what the models projected, even while stratospheric and surface trends are much closer to the ensemble mean. There is still more to be done here. Stay tuned!

The results from CMIP6 (which are still being rolled out) are too recent to be usefully added to this assessment of forecasts right now, though some compilations have now appeared:

The issues in CMIP6 related to the excessive spread in climate sensitivity will need to be looked at in more detail moving forward. In my opinion ‘official’ projections will need to weight the models to screen out those ECS values outside of the constrained range. We’ll see if other’s agree when the IPCC report is released later this year.

Please let us know in the comments if you have suggestions for improvements to these figures/analyses, or suggestions for additions.

References

- Z. Hausfather, H.F. Drake, T. Abbott, and G.A. Schmidt, "Evaluating the Performance of Past Climate Model Projections", Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 47, 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1029/2019GL085378

- G.A. Schmidt, D.T. Shindell, and K. Tsigaridis, "Reconciling warming trends", Nature Geoscience, vol. 7, pp. 158-160, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2105

2020 Hindsight

Yesterday was the day that NASA, NOAA, the Hadley Centre and Berkeley Earth delivered their final assessments for temperatures in Dec 2020, and thus their annual summaries. The headline results have received a fair bit of attention in the media (NYT, WaPo, BBC, The Guardian etc.) and the conclusion that 2020 was pretty much tied with 2016 for the warmest year in the instrumental record is robust.

[Read more…] about 2020 HindsightFlyer tipping

You would be forgiven for not paying attention to the usual suspects of climate denial right now, but they are trying to keep busy anyway.

Last week (January 8), Roy Spencer [Update Jan 13: now deleted] posted a series of Climate Change “flyers” on his personal blog that purported to be organised by David Legates (NOAA, detailed to Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), nominally on leave from (and soon to return to) U. Delaware). Each was a rather garishly colored rehash of standard climate denial talking points, but featuring the OSTP official logo, and claiming to be copyrighted by OSTP (a legal impossibility). Note that if this was an official US Govt. work, they could not copyright them, but if it wasn’t, they could not legally use the OSTP logo to indicate that it was.

The reaction to this definitive refutation of mainstream science (ha!) was… silence. Spencer’s post was reblogged at WUWT but again, nothing happened [Update Jan 13: Also now deleted]. . Many of the authors of the pieces themselves – many of whom are active on social media – didn’t bother to tweet or post about them. Odd.

The whole thing seems to be Legates trying to get a pet project out into the world before the new administration comes in, but without bothering with all that messy peer-review, official permission, proper channels or, you know, actual science. Almost certainly this is also a violation of the Data Quality Act, something Patrick Michaels (one of the flyer authors) was quite exercised about in his effort. Consistency is also apparently optional.

Anyway, a couple of days ago (Jan 10), they were also posted on Willie Soon’s new website where they were noticed on twitter, and today there have been some media eyebrows raised.

Is there a there there?

The flyers themselves are remarkably thin on valid argumentation. Will Happer’s discussion of Radiative Transfer is mostly textbook stuff except for the last paragraph where he simply asserts that a radiative forcing of 3 W/m2 can’t possibly matter. That’s kind of the key issue, which he totally elides.

Christopher Essex purports to discuss climate models, without ever showing anything from a climate model. He seems to be arguing against some Aristotelian concept of climate models that never has to be bothered with actually looking at the real world (for instance). Weird, and totally pointless.

Spencer makes the remarkable assertion that climate has changed for natural reasons in the past (I’m shocked, shocked!), and ignores how attribution actually works (I’m not at all shocked).

The Connollys and Willie Soon’s flyer purports to talk about sun-climate connections, but they spend most of their effort talking about Milankovitch forcing before pivoting to imagining a universe where the temperatures have not in fact been steadily climbing but where they could conceivably have a higher correlation to out-of-date and unsupported reconstructions of solar activity. In so doing, they even have the chutzpah to cite a paper of mine. Meh.

Etc. If there is a demand in the comments, I could expand on the others, but for now, I think you get the idea.

Why should anyone care?

Great question! I don’t think anyone should. But this whole effort is emblematic of how far the climate question has moved. With a new US administration poised to act on climate across a whole series of fronts, this feeble throwback (were they released on a Thursday?), serves to underline how out-of-touch these old school deniers and their talking points really are. This is perhaps the last weak ‘hurrah’ of a bankrupt cause.

Good riddance to bad rubbish.

Update (4pm, Jan 12): that was quick:

BREAKING: @WHOSTP has fired climate contrarians David Legates and @RyanMaue days before their last scheduled day of service, due to their role in the unauthorized writing and publishing of controversial climate papers w/ White House markings. https://t.co/3aMhpZJ65w

— Andrew Freedman (@afreedma) January 12, 2021

Unforced Variations: Jan 2021

According to the somewhat* arbitrary customs of our age, the 1st of January marks the beginning of a new year, a new decade and, by analogy, a new start in human affairs. So shall it be at RealClimate too**.

This month’s topics will no doubt include the summaries of the 2020 climate (due Jan 14th or so), ongoing efforts to understand and predict extreme weather in a climate context, and the shift by the weather organizations (WMO, NWS) to a new set of climate normals (i.e. moving from 1981-2010 to 1991-2020).

In the spirit of this new year, please make a renewed effort to stay vaguely on climate science topics, try to stay constructive even when you disagree, refrain from posting abuse, and don’t bother with cut-and-paste climate denial (that stuff was tedious enough when it was originally wrong, and is simply boring now). Thanks!

*completely

**Seriously, we are thinking about how to update/re-position this blog, and would welcome constructive suggestions from readers.